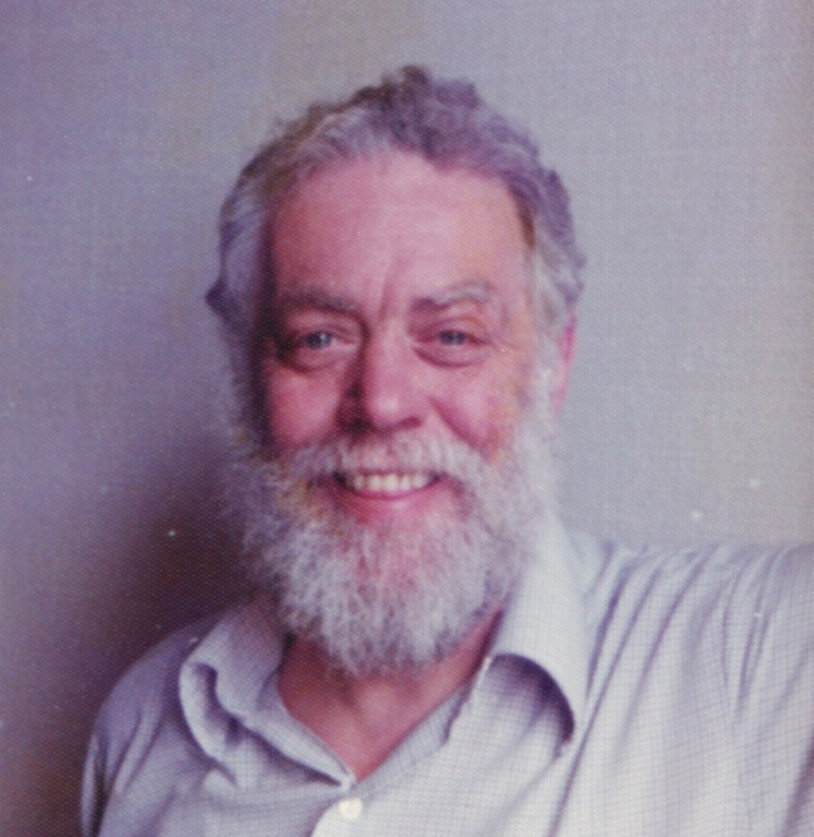

Every inventor has their own unique background, and in my father’s case it was the world of engineering – which probably comes as no surprise, given the precise gearing system of Spirograph !

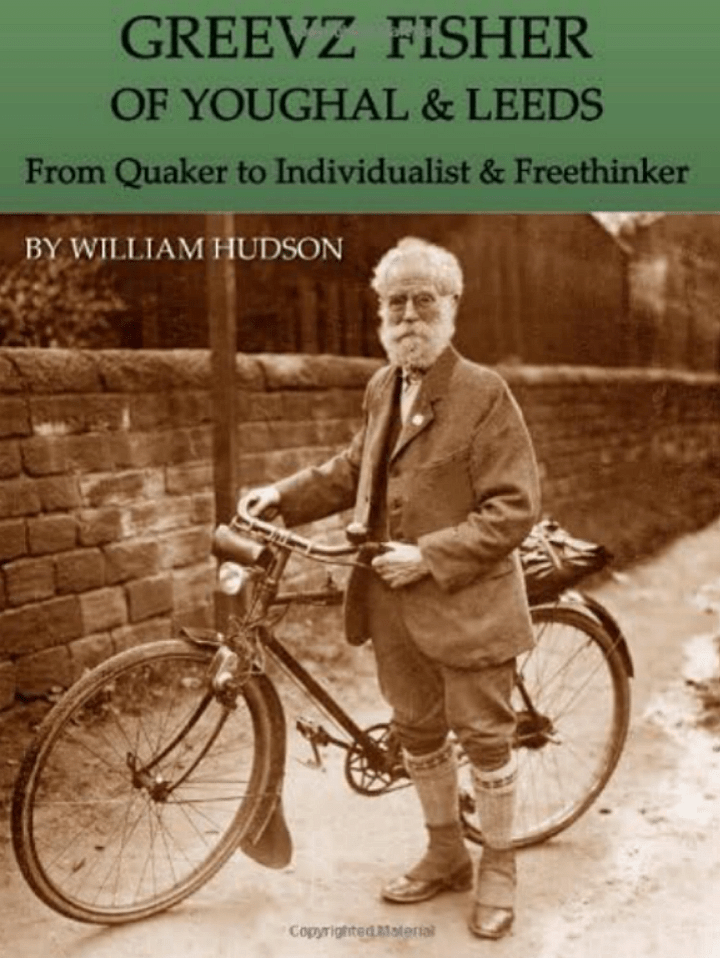

Denys was born into a family of engineers, inventors and freethinkers, a family that was headed by his grandfather, Greevz – a formidable thinker and innovator in his own right – who was the proprietor of the family engineering business: Kingfisher Lubrication (which is still going strong to this day.)

Just like dad, Greevz Fisher was a real character, and he is the subject of an excellent book written by my cousin, William Hudson.

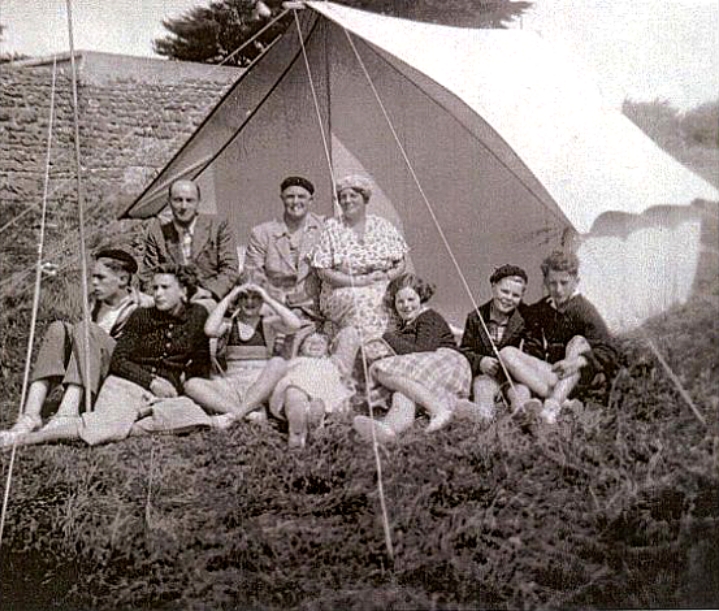

My father was the eldest child of Wordsworth Donisthorpe Fisher (‘Don’ ) and his wife Helen, and it was a humble start in life for Denys as the family home was actually an old railway carriage on the outskirts of Leeds.

Don had bought an acre of land from a farmer, and he and Helen raised dad and his four siblings in the railway carriage they sited on their allotment.

Cue many eccentric tales of off-grid living!

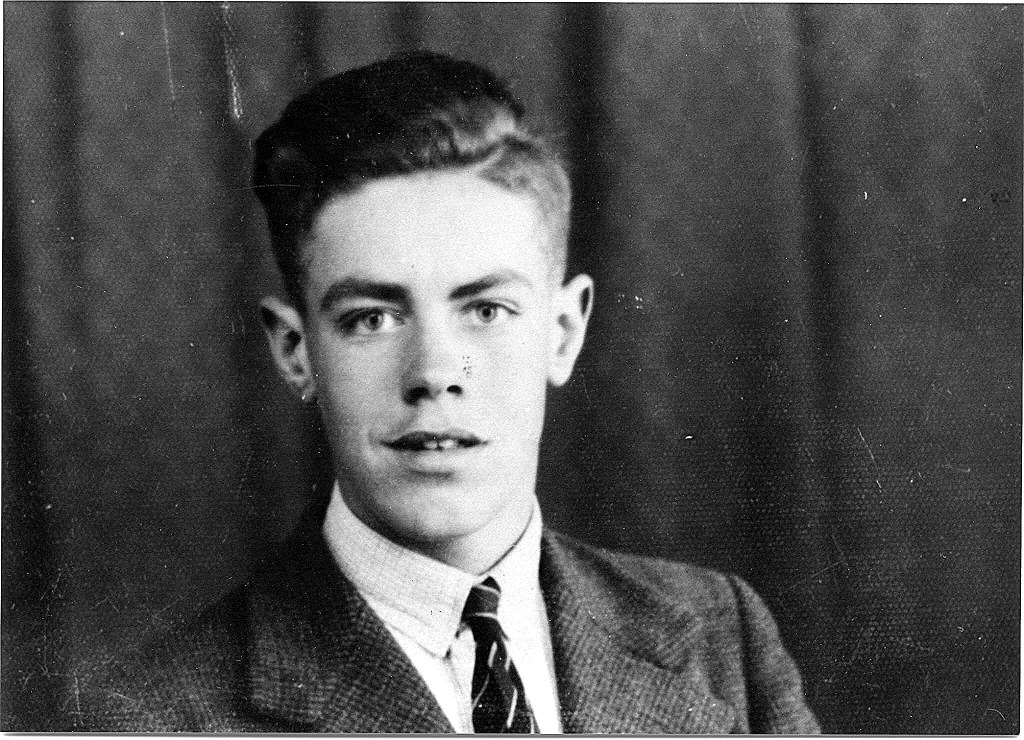

Fast forward to Denys’ teenage years, and he attends Roundhay School where he excels at mathematics, having discovered his passion for the subject whilst quarantining at home with Scarlet Fever. His only reading matter during that period of enforced isolation was Horace Lamb’s “An Elementary Course of Infinitesimal Calculus” – a doughty-sounding tome, but one which inspired a great love of maths in Denys.

School greatly expanded Denys’ intellectual horizons, and while at Roundhay he developed a lifelong love of poetry and literature. Dad excelled at swimming too, and also became a stalwart of the school chess team. Rugger, though, was not to his liking and when a tackle in one match made Denys bite through his tongue he turned his back on the sport!

The University of Leeds was next for Denys – although he chose to read Electrical Engineering rather than his great passion Mathematics. Perhaps his choice of subject was the reason why he struggled on his degree course.

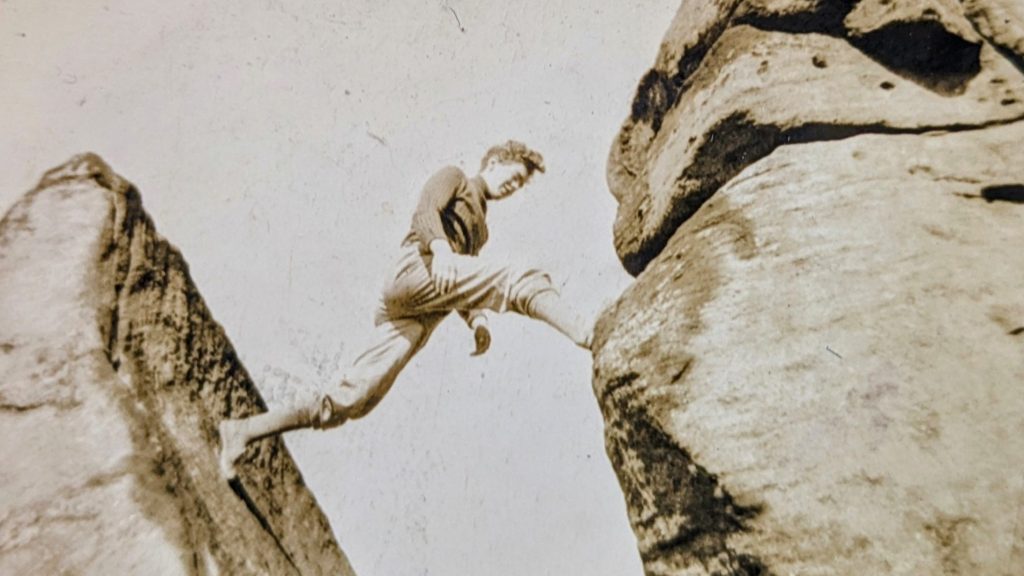

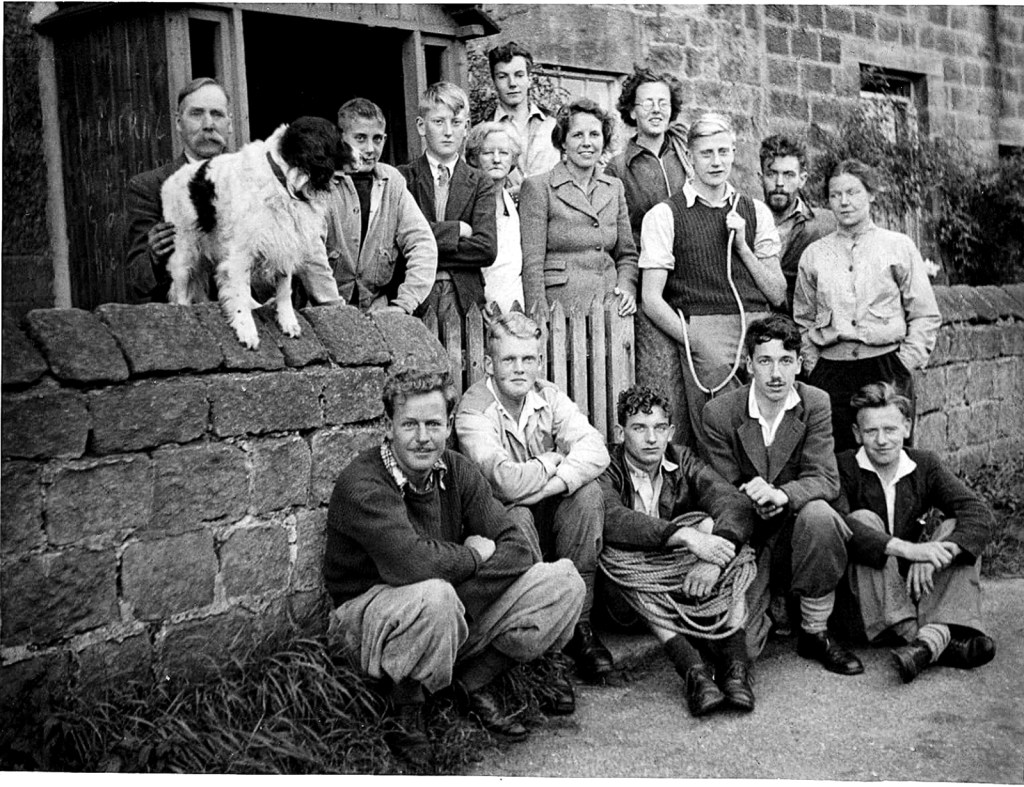

What was going well for Denys at that time, however, was his rock climbing. Dad took to the sport with alacrity after being introduced to it by his university pals, and honed his craft at Almscliffe Crag, the celebrated gritstone outcrop that lies ten miles north of Leeds.

Image credit: Coolug, Licence: Attribution 3.0 Unported

Denys found that he had a talent for climbing, and it wasn’t long before he was putting up his own new routes.

Together with his pals from university, Denys began motorbiking off to the Lake District at weekends where he would climb all the classic routes. Dad told me that these days of freedom on the crags were some of the happiest times of hislife.

For a time, climbing was Denys’ life – to the detriment, perhaps, of his university studies – at which he failed to get a degree.

That was the first major setback of his life, and Denys’ response was to escape to France, where the Fisher family had many friends. There was one friend in particular who dad was keen to see – Lucette – who became his first serious girlfriend while he was working as a farm labourer in France during the summer of 1939.

Of course, 1939 was also the year that war broke out in Europe, and itforced Denys to beat a hasty retreat back to England. Being a committed pacifist, he was not minded to sign up, so my father joined Kingfisher Lubrication – the family engineering business – instead. They were repurposing their workshop for war time contract, which meant that Denys entered a reserved occupation and was no longer eligible for call-up.

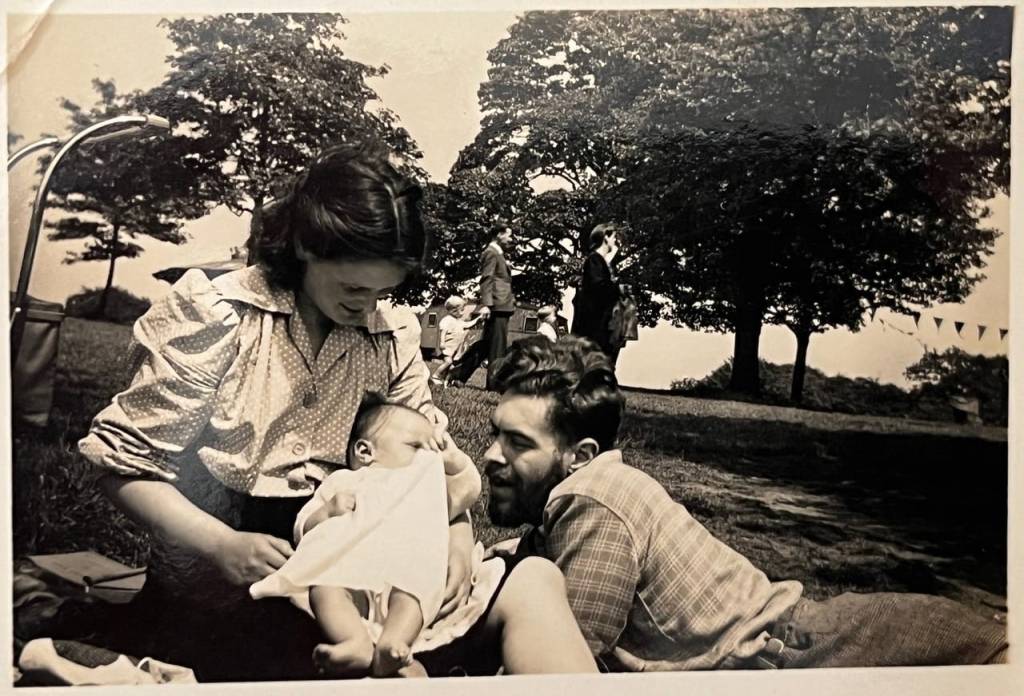

On a climbing trip to the Lakes in 1940, Denys met a Westmorland lass called Betty, and two years later they were married and began setting up home in Leeds.

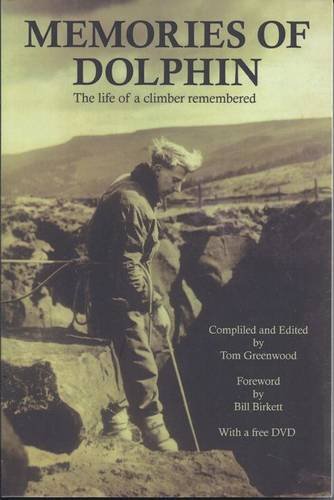

Denys’ climbing exploits continued after his marriage, and a friendly rivalry sprang up between him and an outstanding young climber called Arthur Dolphin, who would go on to become the finest British rock climber of his generation.

Tragically, at just 28 years of age, Arthur Dolphin fell to his death while descending the Dent du Géant in the Alps, and his short life is now the subject of an excellent book called “Memories of Dolphin”.

Towards the end of the war, Denys and Betty welcomed the birth of their first child, Cherry, and after her arrival, dad’s climbing activities faded into the background as he began concentrating on his career as an engineer.

The privations of wartime created an opportunity for an inventive fellow like Denys and he became increasingly important to Kingfisher’s operations through making automatic machinery and tooling for them that couldn’t be sourced from abroad at that time.

The death of Greevz’ widow Marie in 1950, and then Denys’ father Don just six months later, ushered in a changing of the guard at Kingfisher with my father, his brother and cousins all joining the company board.

Increasingly, though, Denys saw no role at Kingfisher for the specialist innovation skills he had developed during wartime so, in 1960, he struck out on his own and established his own engineering business.

Denys Fisher Engineering (Ltd) was a spring and precise component manufacturer whose first significant contract was making calliper springs for Raleigh Bicycles.

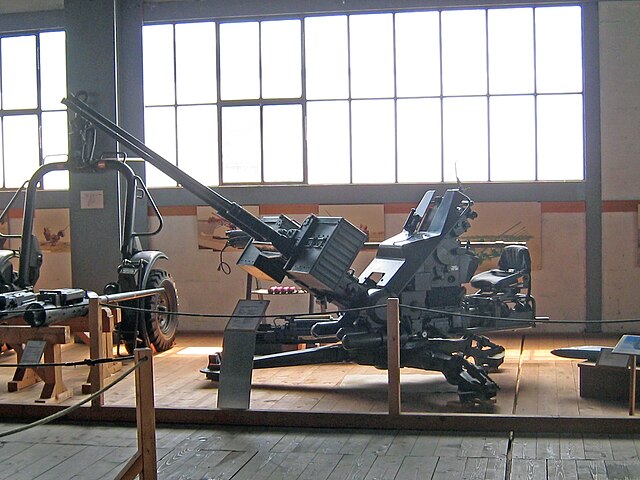

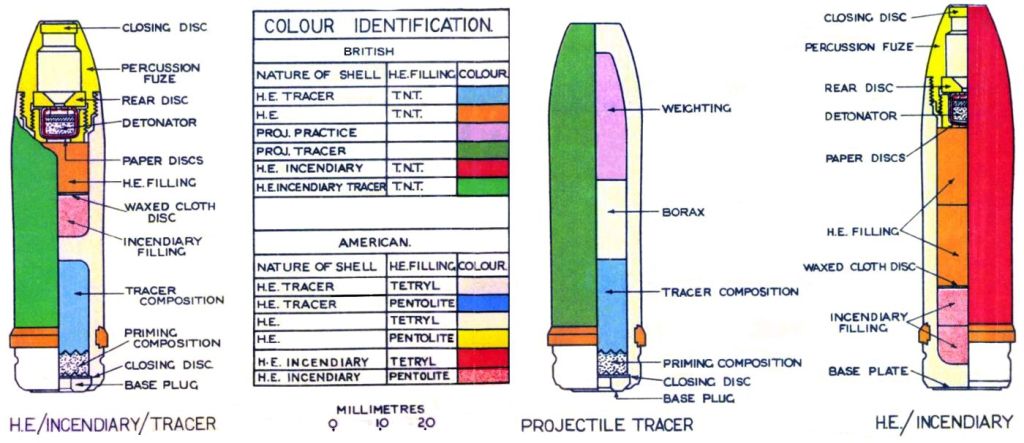

Dad’s next job was even more lucrative – a contract to supply three million detonators for the shells of a NATO 20mm caliber autocannon (which was almost certainly the Hispano-Suiza HS.820.)

Credit:Bunkerfunker Licence: ShareAlike 3.0 Unported – Creative Commons

similar to those that Denys was making precision components for.

But this line of work did not sit easily with Denys, whose personal views always leaned towards pacifism. So he began casting around for another project to get his teeth into, and started exploring the intersection of mathematics with engineering – two of the great interests of his life.

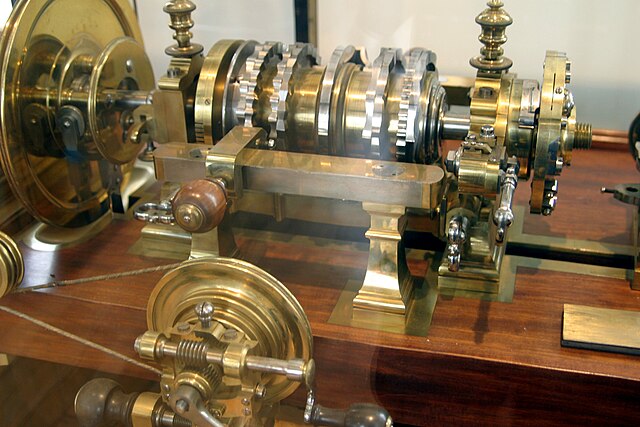

In particular, his mind recalled a fascinating machine he had encountered during his Kingfisher days: the Rose Engine Lathe.

Credt:Rama, Licence: ShareAlike 2.0 France – Creative Commons

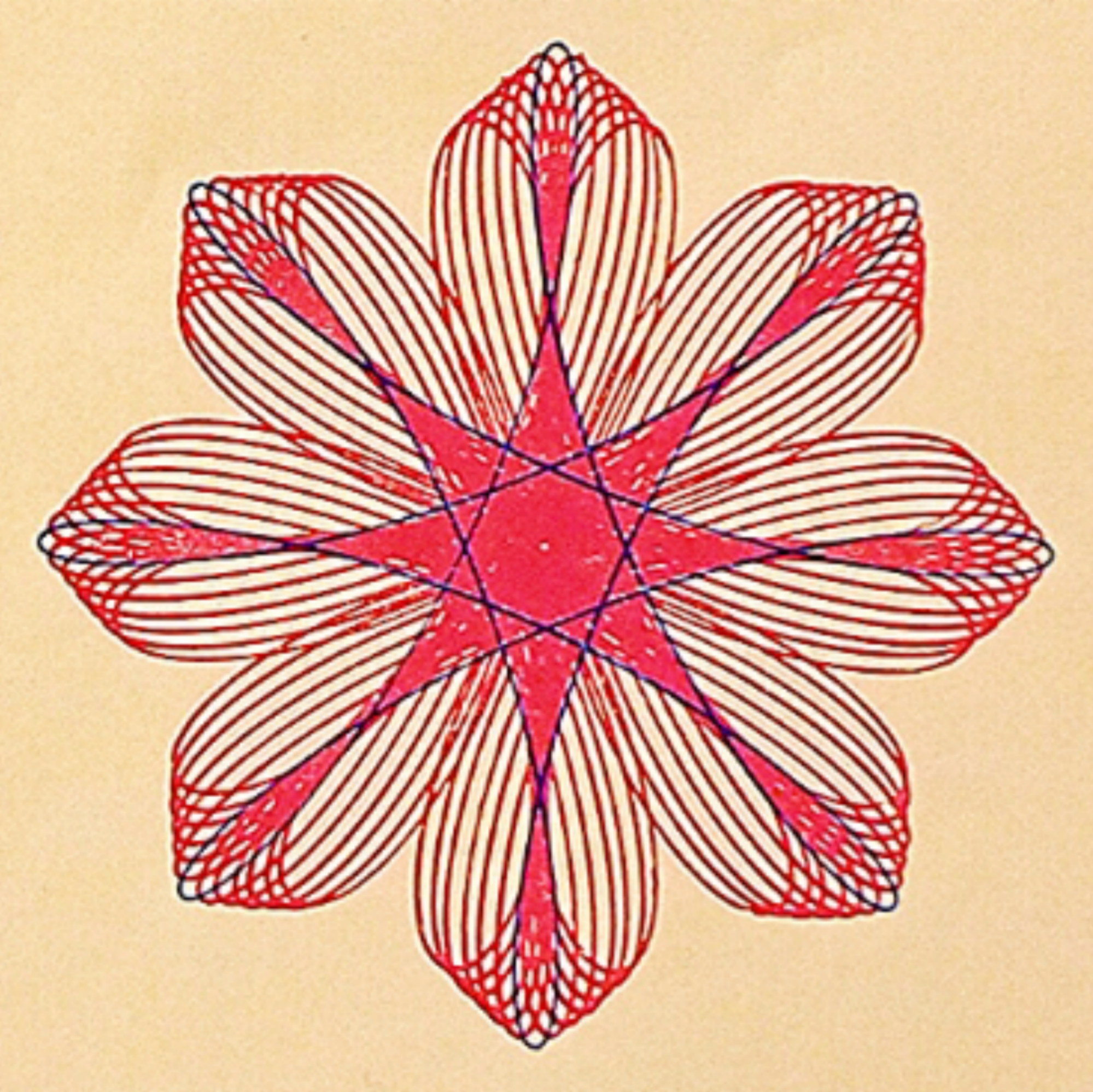

These mysterious machines were used to create complex geometrical patterns on the printing plates for bank notes to help deter forgers, and Denys first saw them in action at Waddingtons Security Printers in Leeds. Naturally, there was quite some secrecy around these Rose Engine Machines and Waddingtons only acquired theirs when De La Rue’s London print works was destroyed during the blitz in 1941, and their operations were evacuated north to Leeds.

Rose Engine Machines were a product of the long tradition in geometrical drawing devices which traces its history at least as far back as 1752 when Giambattista Suardi described his ‘Geometric Pen’.

To be continued…..!

Share this page

Have a comment? Let me know!